When Bone Density Isn’t the Full Story:

How a Knee Fracture Reframed My View on Osteoporosis, Ethics, and Movement

“Bone health isn’t just a number on a DEXA scan, it’s the unseen architecture, the scaffold that actually keeps you standing"

The day before my annual vacation, a much-anticipated trip to Spain, I felt a sharp sting on the inside of my knee during a routine movement, nothing dramatic, just an inconvenient sprain I assumed would settle. But in the days that followed, as I masked it with anti-inflammatories, Panadol, and the occasional Sangria, something else was happening in the background.

A recent Substack article that I posted on flexion, disc height, and ethical movement had opened a much bigger conversation - your comments, questions, and messages about bone density, fractures, and medication options. As I moved from holiday to MRI, from orthopaedic appointments to a rheumatology consult, the parallels between my personal experience and the questions readers were asking became impossible to ignore. This article is the follow-up that grew out of both.

The Kind of Fracture That Doesn’t Require a Fall

After returning home and easing back into normal life, the knee pain changed character. It no longer behaved like a ligament injury. It had a deeper, more internal quality, a pain that didn’t quite make sense for a sprain.

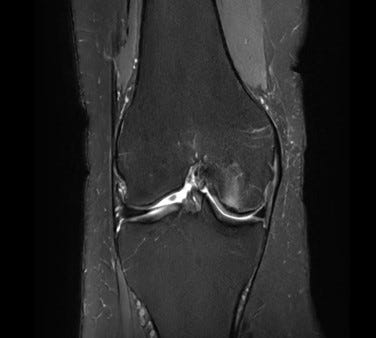

An MRI finally explained why: a subchondral insufficiency fracture of my femoral condyle. (The white shadowy image seen receding from the cartilage)

A fracture without impact.

A break without trauma.

A structural failure rather than an accident.

A subchondral insufficiency fracture (SIF) occurs just beneath the cartilage surface, at the load-bearing platform of the joint. These fractures aren’t caused by a dramatic event, they happen when normal forces exceed weakened bone architecture.

They are biomechanically similar to vertebral endplate microfractures and wedge fractures:

standard forces

compromised trabeculae

microscopic failure

escalating pain

risk of collapse if unmanaged

It is the same underlying mechanism seen in osteopenia and osteoporosis.

Density plays a role, but architecture is what fails.

Two Surgical Opinions—And a Third Path I Didn’t Expect

I sought two orthopaedic opinions.

The first walked through surgical possibilities but with visible hesitation. Technically possible, yes. Ideal? Not at all.

The second surgeon was more direct: “There’s nothing I can do surgically to fix that.”

It wasn’t hopeless, it was honest.

This wasn’t a mechanical tear. It was bone insufficiency. Operating on the surface wouldn’t change the underlying weakness.

Then a longtime client of mine, someone with an exceptional medical reputation suggested a different route. He connected me with a consultant who examined the imaging, asked incisive questions, and immediately reframed the issue:

“This is a bone-architecture problem. We need to rebuild the structure.”

He prescribed Romosozumab for 12 months, followed by bisphosphonates to maintain the gains.

And suddenly, my personal detour aligned perfectly with the big questions many of you asked after my recent article.

What My Knee Has in Common With the Spine

In my previous Substack, I explored how loss of disc height alters load distribution, increasing stress on the anterior vertebral body and raising the risk of wedge fractures, even during everyday bending.

The pattern is identical across sites of fragility:

femoral condyle

vertebral body

sacrum

calcaneus

many more locations

Each of these areas relies on dense, interconnected bony struts to distribute load.

When those networks thin or disconnect, ordinary forces create microdamage.

Most people think of fractures as failures of bone quantity, ie. low bone mineral density. But the deeper truth is that many fragility fractures happen because of failures in bone quality:

reduced bony strut thickness

fewer load-bearing struts

loss of horizontal connectivity

accelerated microcrack accumulation

This is why someone can have only mildly reduced bone mass density, and still sustain insufficiency fractures, exactly like mine.

Meet the Three Bone Allies in My Story

1. Romosozumab (Evenity) – “The Builder”

2. How it works: Blocks sclerostin, allowing bone-building cells to increase bone formation, and indirectly reduces bone-reducing activity to slow resorption.

Lay analogy: Imagine your skeleton as a brick wall. Romosozumab adds new bricks while slowing the removal of old bricks, making the wall thicker and stronger.

Structural benefits:

Thicker bony struts

More bony struts

Stronger connectivity

Improved bone strength

Supports load-bearing joints (like the femoral condyle), vertebral bodies under anterior compression, and other sites

Why it’s used first: Because it actively rebuilds fragile bone, creating the scaffold needed for durable strength. Usually given as a monthly injection for 12 months, then followed by another therapy to lock in gains.

2. Bisphosphonates – “The Protector”

How it works: Slows the breakdown of bone by embedding into the mineral matrix and reducing bone reabsorption activity. They don’t build new bone, but they preserve what you already have.

Lay analogy: Think of your skeleton wall again. Bisphosphonates act like a sealant, preventing existing bricks from crumbling.

Why used after Romosozumab: Once new bone is built, bisphosphonates lock in those gains, maintaining stronger bone for the long term.

Key point: Can be taken weekly, monthly, or yearly, depending on the specific medication and medical guidance.

Evidence: Major studies show that Romosozumab → Bisphosphonate produces the strongest and most durable gains in bone density and strength. Doing the sequence in reverse blunts the effect because the bone is metabolically quiet.

3. Denosumab (Prolia) – “The Pause Button”

How it works: Blocks Receptor Activator of Nuclear Factor Kappa-B Ligand (RANKL), slowing bone breakdown, similar to bisphosphonates but via a different mechanism.

Lay analogy: Like pressing the pause button on bone loss, letting existing bone remain intact while the body slowly repairs itself.

Differences from bisphosphonates: Works more quickly, requires injections every 6 months, and bone loss can rebound if treatment stops suddenly; follow-up is critical.

Why Sequence Matters

Build first (Romosozumab) → Protect second (Bisphosphonates) → Optional pause/maintenance (Denosumab).

This approach maximises structural gains in bone, which is critical in high-risk areas: femoral condyles, vertebral bodies, and other weight-bearing sites.

Sequencing ensures the newly formed bone is consolidated, rather than losing the gains due to suppressed metabolism or abrupt therapy changes.

Connecting This Back to the Spine and Safe Movement

Even with stronger bone, how we move matters:

Disc height

Posture

Movement habits

Force vectors

Hip mobility

Thoracic stiffness

Medication can improve bony integrity, but it cannot change how we move through gravity. If disc height shrinks, anterior vertebral forces rise. Habitual forward bending increases the load further, so fracture risk can rise again. Bone strength and movement strategy must evolve together, which was a key lesson from my injury.

My Plan Going Forward

Here’s what my long-term approach looks like:

1. Rebuild Architecture - 12 months of romosozumab to repair structural deficits in the bone.

2. Consolidate the Gains - Transition to bisphosphonates to stabilise the newly improved architecture.

3. Monitor Biology - Regular bloodwork and bone turnover markers to ensure appropriate response.

4. Move Intelligently

Not fearfully - intelligently.

Protecting the knee while loading it progressively.

It’s not restriction.

It’s precision.

A More Mature Philosophy of Bone Health

Bone health is not a quest for higher numbers on a DEXA scan.

It is the intersection of:

structure

turnover

load distribution

medication strategy

biomechanics

and intelligent movement

It is accepted that building bone is the first step, but protecting it and moving wisely are what keep fractures from returning.

My knee fracture wasn’t convenient, but it was clarifying. It connected the science, the practice, and the lived experience in a way I couldn’t ignore.

And it reminded me that the most effective approach to bone health is not singular, but layered:

Build what’s missing.

Protect what’s built.

Move in ways that respect the forces that shape us.

That, more than anything, is the real follow-up to the conversation we started together.

Quick Jaw Check: A very rare side effect of some bone medications (denosumab, bisphosphonates) is osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), where jaw bone struggles to heal. In typical osteoporosis treatment, the risk is extremely low; roughly 1 in 10,000 to 3 in 10,000 patients per year. Risk rises with high-dose therapy, dental surgery, or poor oral health. Maintaining good dental hygiene and consulting your dentist before starting therapy are standard precautions.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is for educational and informational purposes only. I am sharing my personal experience, research, and reflections; not medical advice. I do not prescribe medications, diagnose, or treat medical conditions. Any discussion of romosozumab, bisphosphonates, or other therapies is based on published evidence and my own consultations with healthcare professionals. Always seek guidance from a qualified medical practitioner before starting, stopping, or changing any treatment.

Back